HOME DUST JACKET REVIEWS CHAPTER 1 CORRECTIONS PRESS RELEASE ORDER the BOOK |

ASSESSING THE VIABILITY OF A PALESTINIAN STATE

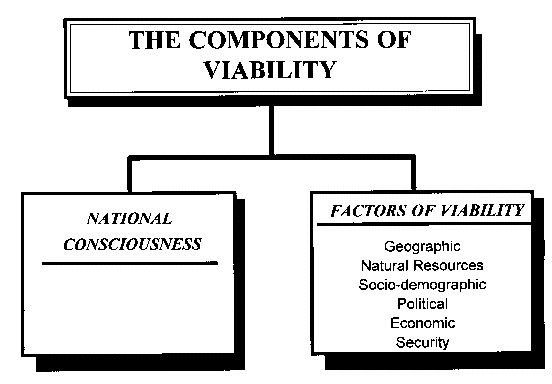

"Viable" literally means "able to live." In the wild, a viable colony of animals or plants is one that has enough individuals and a sufficiently large gene pool to guarantee survival of the group in the face of the normal hazards of its surrounding environment. Politically, Webster's Dictionary defines the word to mean: "capable of existence and development as a relatively independent social, economic, or political unit." 1 In the course of this research, some have suggested that legitimacy and sovereignty might be related to the concept of viability. Legitimacy is, however, only distantly connected, since it pertains primarily to whether a given people accept a leader or government as lawful or right. Sovereignty, however, is directly related. "Sovereignty may be defined," states political scientist Frederick H. Hartmann, "as the ability of the state to make independent decisions."2 If we accept this, then perhaps it can be said that viability is the capacity to maintain sovereignty indefinitely. With this in mind, I propose the following as a working definition for "national viability": The ability of a nation-state to survive with its own resources as a discreet, identifiable entity, not dependent for its survival on any necessary organs of statehood belonging to any other nation. By this definition, the United States would be a viable nation, as would Egypt, India, Japan, Chile, New Zealand, and all other sovereign nations around the world. Each of these nations might have significant social, economic, or other problems, and may in varying ways be dependent on other nations (for rare metals, specialty consumer goods, laborers, etc.) to maintain certain activities and qualities of life. Yet they retain within their existent national institutions all the essential processes and resources to maintain their gestalt as an independent nation-state. In contrast, the Principality of Liechtenstein likely would not be a viable nation-state in and of itself, since it lacks the mechanisms to survive were it suddenly severed from the Swiss economy and infrastructure. Nor has it the resources to develop such infrastructure on its own. One might use the analogy of Siamese twins, where one twin shares vital organs with its fellow, making separation impossible. Additional examples of regions possessing some of the measures of nation-hood, but which in the end would probably fall short of the necessary "critical mass" for achieving an independent state are Kurdestan, the Basque areas of Spain and France, and portions of several African nations. We must, of course, be careful here not to let the status quo become our definition by assuming that the sovereign nations existing today must necessarily be all that can be viable, while any area that hasn't achieved sovereignty must not have what it takes. In general, it is likely that most, and perhaps all, nations having the necessary components to be self-sustaining do already exist. Conversely, any region having insufficient of those components will probably remain a subordinate portion of some other country. However, it is possible that certain regions and peoples exist that if allowed and (where necessary) properly facilitated, might successfully form viable sovereign nations. Certain of the South African homelands might fall into this category, as well as many of the former Soviet republics, and, of course, Palestine. To evaluate this potential, we must go now beyond the definition of viability to an exploration of its components parts. COMPONENTS OF VIABILITYI propose that the nature of viability is defined by two major components, which I have designated "National Consciousness" and "Factors of Viability." Both these components must be present for a nation-state to exist. For example, all of the necessary factors may be present to create and sustain a nation-state, yet if a people has no awareness or consciousness of being a national entity, unique and apart from any others, no nation will result. Conversely, a people may consider itself a national entity in every respect, yet if the essential viability factors either are not present or cannot be developed, the people will be unable to form a survivable nation. National Consciousness Modern developments in computer technology and the search for artificial intelligence have sparked renewed philosophical speculation as to what constitutes "consciousness." As humans we intuitively understand consciousness, but don't know empirically what it is, nor can we yet separate out the ingredients that cause it to exist. Often the presager of things that later become reality, the science fiction genré has played with the idea of consciousness. Some clever stories suggest consciousness as a phenomenon that occurs when enough subcomponents of a computer begin to interact, or "communicate," to achieve a certain threshold or critical mass, creating something that is not only more than "the sum of the parts," but that actually becomes aware of itself as an individual separate from the environment around it. These stories postulate a machine designed to be so intelligent that once the master switch is flipped, it literally "comes alive" mentally. One can almost envision a "consciousness" or "awareness" metaphorically coming to an invisible hover slightly above and among all the blinking lights and whirring gizmos, once power is turned on. This analogy makes surprising sense in terms of nation-building. In the early 1950's, political scientist Karl Deutsch discussed principles in the development of the nation-state that anticipated such concepts. Deutsch's ideas would be familiar to computer and artificial intelligence specialists. Seeking to analyze just what makes a nation what it is, he proposed that one of the primary steps toward "nation-ness" is developing an awareness of having a "common history" as a community. In order for this history to be experienced as common to all others in the community, "facilities of communication" are necessary, which, according to Deutsch, perform a certain "job": This job consists in the storage, recall, transmission, recombination, and reapplication of relatively wide ranges of information; and the "equipment" consists in such learned memories, symbols, habits, operating preferences, and facilities as will in fact be sufficiently complementary to permit the performance of these functions. A larger group of persons linked by such complementary habits and facilities of communications we may call a people. (Emphasis in original)3 The "memories, symbols, habits, operating preferences, and facilities" could by analogy represent the huge volume of stored data in our fictionally sentient computer. When this "data" is subjected to "storage, recall, transmission, recombination, and reapplication" through links of communication, it is integrated into the community's consciousness just as it is in our computer analogy. If the available data is abundant enough, and if the "neurons" (the individual units of the community--people, families, organizations, institutions, etc.) are sufficiently numerous, and if these "neurons" are adequately interconnected for the sharing of information, a national consciousness can result. Deutsch proceeds further to illuminate the notion of nationality, which "essentially consists in wide complementarity of social communication," and the "ability to communicate more effectively, and over a wider range of subjects, with members of one large group than with outsiders."4 Once a people exists as a national entity, "the range and effectiveness of social communication within it may tell us how effectively it has become integrated, and how far it has advanced, in this respect, toward becoming a nation."5 Social communication can be likened to the integrated circuitry of our notional computer. Deutsch explains that the proximity and clustering of human settlement patterns and geographic distribution of the populace effect the identity-forming process to the degree that it facilitates this communication. Nationality is finally created when "large numbers of individuals from the middle and lower classes" develop strong linkages among themselves and with regional population and industrial centers, while simultaneously becoming strongly affiliated with social elites, which will provide the necessary direction and leadership through "channels of social communication and economic intercourse." These connections extend both indirectly from link to link (i.e., locally or regionally), "and directly with the center" of the society.6 Finally, "nationalities turn into nations when they acquire power to back up their aspirations."7 Deutsch's thoughts echo those of John Stuart Mill: A portion of mankind may be said to constitute a nationality if they are united among themselves by common sympathies which do not exist between them and any others--which make them cooperate with each other more willingly than with other people, desire to be under the same government, and desire that it should be government by themselves or a portion of themselves exclusively.8 A people, as Frederick Hartmann states, "must have a common outlook at least to this extent: that they agree they are a distinct group who ought to be governed by themselves and as a group." What sort of government actually does the governing is less important, but the sense of "being part of a group for purposes of government is at the root of nationalism everywhere."9 Nationalism, of course, is a subject much studied in the Twentieth Century, and is considered an essential ingredient in the development of an emerging nation-state. What I describe as "national consciousness" bears much in common with the concept of "nationalism," yet they are not the same. Nationalism could be thought of as the yearnings and political motivations toward having a state of one's own, while national consciousness encompasses not only the precursors of nationalism, but all the ancillary elements of being aware of and participating as a member of a people/nation. Indeed, national consciousness could be thought of as the parent to nationalism. As phenomena, neither nationalism nor national consciousness can be measured. But their presence can be demonstrated by the behaviors and beliefs within a people being examined. National consciousness manifests itself when a people sees itself as different from all others. This people speaks of having its own customs, traditions, crafts, folk ways, and weltanschauung (or view of and relation to the external world). Its members work and band together when threatened, and tend to engage in commercial and social intercourse with one another. The members feel politically allied, though they do not necessarily always agree on how those politics should be manifest. They perceive themselves as stemming from common origins, and feel connected to the same formal and informal social institutions. Though there may be a number of social or economic strata in the society, often separated by wide gaps, intangible yet undeniable bonds still exist to make everyone allies in questions of what makes "Us" who "We" are. A certain piece of land or territory may enter into the equation--in fact usually plays a significant part--but this is not in every case crucial to the development of national consciousness. Land becomes essential, however, when nationalism develops. "The world in which [we] live," notes one observer, "is a world of nation-states. . .[and] relative normality in a world of nation-states can only be attained by having one's own nationality reflecting itself in one's own national homeland."10 The presence of nationalism in a people is obvious in their demands to be left alone, independent in their own territory. They seek for sovereignty, for autonomy, for the right to self-determination. Sometimes they succeed in their quest as did the Israelis; sometimes they fail, as have, so far, the Kurds. But having reached this stage they have achieved half the equation for national viability. The second half of the formula follows. Factors of Viability To be useful, the study of international relations must provide insight into the character of nations, their relationships with one another, and how these relationships are manifest in the international environment. Examining any given nation as an actor in the world requires an evaluation of what facilitates and what hinders it in obtaining its needs, and what mechanisms it has available to influence other nations to its advantage. The force or influence a nation can wield in its own interest has become known as "national power," and has been the focus of considerable study attempting to first define it, then in some meaningful way measure it. So far, the most practical approach for exploring the concept of "national power" has been to reduce it to its component parts, or "elements," which are then used to evaluate the subject country. However, no two experts can agree completely on what the elements are, or how to measure them. Much has nevertheless been learned about nation-states. Many of the factors that underlie national power seem to be strongly related to elements of viability, and although the correspondence is not exact, there is enough of a correlation between them to allow us to use tools created to research national power as a springboard in exploring viability. A number of people have attempted to define national power. One notable effort by Ray Cline created a quasi-mathematical formula combining factors of population, economics, military, and national will to provide a roughly quantitative analysis of national power.11 Because Cline's aim was to rank-order nations according to their power in the international arena, with a significant focus on strategic weapons and power projection, his methodology is of less value for our discussion. Another, more useful, approach was contributed by the widely-respected Hans Morgenthau. In his definitive book, Politics Among Nations, Morgenthau defined national power in terms of nine elements: Geography, Natural Resources, Industrial Capacity, Military Preparedness, Population, National Character, National Morale, Quality of Diplomacy, and Quality of Government.12 Several of these elements have sub-elements--under Military Preparedness, for example, falls "technology," "leadership," and "quantity and quality of armed forces," while "distribution" and "trends" are sub-categories under Population. Morgenthau used these nine elements as a framework for understanding a nation's ability to both protect its interests and project its will. However, like Cline, Morgenthau's focus was primarily from the nation outward into the international milieu, so some of his elements are extraneous to the present discussion, while he misses others that are crucial. As one example, under population he is most concerned with the relative size and quality of a nation's population when compared with other countries. The viability question, however, is more concerned with internal and less with external comparisons. His discussion of military preparedness focuses on a nation's ability to defend itself and project armed force beyond its borders; force projection is less relevant to viability. Conversely, though he would likely agree such issues also impact on national power, Morgenthau devotes little attention to internal concerns such as cohesiveness of a population or the state's ability to maintain internal security, which are fundamental viability issues. Other scholars also find this approach to national power useful, though each defines these elements somewhat differently, and includes differing numbers of them. Frederick Hartman in The Relations of Nations suggests six elements of national power: Demographic, Geographic, Economic, Historical-psychological, and Organizational-administrative.13 Seemingly, only one of these, Geographic, matches directly any of Morgenthau's. However, a closer examination reveals that Hartman has merely rearranged many of Morgenthau's subelements into differently-named categories. For example, Hartman's "Economic" element includes "raw materials," for which Morgenthau has a separate category ("Natural Resources"), while his "present and projected production rates" would fall into Morgenthau's "Industrial Capacity" category. Werner Feld, on the other hand, uses seven elements to analyze "the actual and potential power of the state."14 These are: Geography (within which Feld includes natural resources), Population, Economic development, Science and Technology, Traditions and social psychology, Government and administration, and Military organization. David N. Farnsworth has his own six elements which include Geographic, Population, Military Strength, Economic Strength, Natural Resources and Intangible Elements.15 Table 1 compares the various sets of elements and their subelements. For this paper, I will merge some of these elements and modify others into six new categories, at the same time broadening the internal focus to reflect the change in emphasis required to explore viability. In place of the word "element" I will substitute "factor," since for me "factor" implies a more actively inter-related and integrated role, while "element" seems more passive and isolated. These "Factors of Viability" are Political, Economic, Security, Socio-demographic, Natural Resources, and Geographical. Each of these categories has a number of sub-factors to facilitate more detailed analysis of the viability factor concerned: under the Socio-demographic factor, for example, are such sub-factors as "language," "ethnicity," "Religion," "culture and acculturation," etc. Note that there is rough correlation in name with several previously discussed elements of national power, though "Military" has been replaced across the board by "Security." But there are significant internal differences between sub-elements and sub-factors. By way of example: where under Geography Morgenthau concentrated largely on the importance of external geographical barriers in promoting and safeguarding national power, Hartman included population distribution and climate, and Farnsworth added topography. The Geographical viability factor, however, considers a range of topics embracing a wider variety of the "national power" subelements, such as climate, terrain constraints on trade and communications, general topography, ocean access, etc. Few individual sub-factors under each viability factor are indispensable in and of themselves--the aggregate is usually what matters. Each individual factor, set of factors or sub-factors and variables impinge on all the others. As each variable alters or is altered, consequent changes may occur in other categories. Weaknesses or shortfalls a nation may experience in some areas may be adequately made up in others. By analogy, exploring the viability issue is much like a computer spreadsheet program--as each value is changed, all subsequent data must be recalculated to take the new information into account. This means that a particular nation may score very low in a particular area, and yet still be viable if the shortfall is compensated by a strong showing elsewhere among the viability factors. Some lacks, however, are insurmountable. As one obvious example, a country with no water and no means to obtain it could not only not survive, but could never come into existence in the first place. Adequate water is an absolute necessity for viability. Yet a country that has no smelterable ores or whose bureaucracy thrives on baksheesh may still be survivable if it has a strong economy and can import necessary raw materials, or has an inventive population that has learned to work around the government. However, a country with a host of low-scoring sub-factors--weak leadership, few raw-materials, a multilingual and multiethnic demography, religious strife, a harsh climate with short growing seasons--could well be in trouble from a viability standpoint. The more categories in which a nation has a poor showing, the less likely to be viable it will be. A discussion of each viability factor follows.

The Geographic Factor Borders. Ideal borders make an unmistakable demarcation of the frontiers between nations. Well defined borders avoid a large majority of conflicts over disputed territory. They also provide barriers to hostile forces and bolster a country's defenses. Morgenthau notes the correlation between the essentially open borders of Russia and Russia's history of frequent invasions by enemies from the west. He contrasts this with Spain, which has been spared a similar fate by the rugged Pyrenees mountains which all but separate it from Europe.16 What makes "good" borders, though, can be a relative thing. While providing defense, good borders should not pose significant obstacles to peaceful trade and travel. While providing a useful defense against invasion from the north, Spain's mountains also isolated it to an extent from the fertile cultural and economic currents that percolated through Europe. Terrain and topography. Although they play an important secondary role in a nation's climate, terrain and topography are primarily significant as they effect internal communications and trade. Difficult terrain, such as impassable mountain ranges or large, unnavigable bodies of water hinder social integration and increase the cost and energy required for internal commerce. Portions of a nation's territory relatively cut-off from the rest of the country may tend to form closer ties with neighboring nations rather than with their own, leading to internal conflict and instability. Albania, for one, has had this experience with its Albanian nationals living on the far side of the mountains it shares with what was formerly Yugoslavia. Pakistan was an extreme example of this when it tried to maintain control of its former province, Bangladesh, despite the two being separated by the entire Indian sub-continent. Climate. "The single most important geographical factor is climate," Hartmann maintains. "All the world's present great centers of power lie in zones that have sufficient rain and heat to grow crops."17 Climates harsh to either extreme, with either too little or too much precipitation can adversely effect a nation's well-being. Location. A nation's location in relation to other nations can greatly effect its development and survivability. Relative isolation from trade routes or international commercial centers once could have been problematic. Modern transportation and communications technology makes some aspects of this problem less significant. However, location with regard to who one's neighbors are can be an even greater problem. Poland and Belgium have for centuries been a thoroughfare for armies attacking between east and west Europe. The territory now comprising Israel and the occupied territories has had the same experience. The United States, on the other hand, has benefitted by being protected on two sides by wide oceans which serve as highways for trade, but offer formidable barriers to enemies. Mexico's proximity to the US has been both a blessing and a curse at various times over the past two centuries; it both benefits and suffers economically, politically, and socially. Major drainage systems. Large river or lake systems can provide great benefit to a nation or be a major liability. They can, if navigable, be an economical means of travel and commerce, like the Mississippi system in the US or the Rhine in Europe. They can provide large quantities of irrigation water to otherwise marginal or altogether useless land, as do the Nile in Egypt or the Colorado in the western United States. But if not navigable, they may prove a hindrance or an obstacle to communications, development, and commerce, such as the huge swampy regions of the Sudan or Iraq. Ocean Access. As Paraguay and Switzerland attest, access to the sea is not a prerequisite for national survival. Nevertheless, ocean access is of such importance economically and geopolitically that an overwhelming majority of the world's nations place great emphasis on outlets to the ocean. Denial of access or attempts to gain it have sparked major wars in the past. One of the causes of the 1967 Arab-Israeli war was the Egyptian closing of the Straits of Tiran. Gaining or protecting ocean access was an important element in Iraq's war against Iran and invasion of Kuwait. The Economic Factor Work force/Labor Pool. Quality and availability of all grades of labor from skilled through professional are crucial for national development and survivability. Unskilled and semi-skilled workers often today are in short supply, as exemplified by the many developed nations who import such labor from Third World nations to perform basic services necessary to keep their economies running. It is economically important to have an abundant labor supply, but it is also highly desirable to have sufficient jobs for most or all of the population to keep the economy operating optimally, enable citizens to be economically productive instead of burdensome, and to avoid internal dissatisfaction and disruption. Proper work force distribution and categorization are essential, so that disruptive over- and undersupplies in various labor and employment pools and categories can be avoided as much as possible. Available labor resources, of course, are based on demography. Population trends directly influence the size and quality of the available labor force. Industrial Base and Construction. Raw materials and natural resources are useless unless they are reasonably and economically accessible. Of still greater importance, however, is having an industrial base that can make good use of available raw materials. Hartman observes that "economic resources do not in themselves mean great economic power."18 The reason, Morgenthau explains, is that "the lack of an industrial establishment" to deal with "the abundance of raw materials" is a prime cause for significant "lags" in a nations's economic power.19 Agriculture. The closer a nation comes to feeding itself, the more stable it is likely to be, and the more energy and financial resources it can spend on social and economic development. "A country," maintains Morgenthau, "that is self-sufficient, or nearly self-sufficient, has a great advantage over a nation that is not and must. . .import the foodstuffs it does not grow, or else starve." He notes that "a deficiency in home-grown food has. . .been a permanent source of weakness," for both Germany and Britain.20 Though certain finite elements underlie the basic equation of agricultural sufficiency--land area, soil quality, climate, water--availability and industriousness of the portion of the population engaged in agriculture, coupled with the sophistication of the methods and infrastructure devoted to it play a major role and indeed can dramatically effect the yields from identical pieces of agriculturally useful land. Because of modern developments in transportation and distribution of food stuffs, agricultural sufficiency is not essential to viability. Yet it can have dramatic impact on survival dependent on other factors in the survival equation. Financial Infrastructure. Without access to capital, a modern economy cannot develop. Without an expeditious means of transferring and exchanging funds, progressive commercial enterprise cannot occur. Without an establishment for interfacing with the international financial community, trade cannot take place. The presence of or the ability to develop extensive financial expertise, sophisticated, well-regulated financial networks, and the institutions that provide the actual physical and fiscal infrastructure are essential for national survival in the modern world. Communications and Transportation Infrastructures. No country can survive adequately today without efficient, extensive lines of communications. Telecommunications and data networks, good quality roads and rail systems, radio, television and print media resources are all essential to successfully integrate a nation commercially, socially and culturally. Where adequate infrastructure does not exist, it must be developed as one of the initial priorities of a new government. Commerce and Trade. Trade and commerce are ultimately the economic life blood of a nation. Internally, the population must develop a healthy and widely diverse range of goods and services that are exchanged, sold and bought to generate the economic resources and demand necessary for an economy to progress. Externally, import and export are crucial in bringing needed money into the country, as well as essential goods and materials unavailable domestically. A negative balance of trade, caused by more imports than exports, can be economically dangerous, however, and must be guarded against. Water and Power Distribution Infrastructures. A nation's water and power infrastructures are effected by political and economic variables. Yet they in return have direct impact on the economy, health issues and quality of life. Natural Resources Smelterable ores. Availability of the ores that have traditionally fed heavy industry--iron, manganese, tin, aluminum, copper, etc.--have long been indicators of a nation's economic and political strength. The more these ores are present, the more secure a nation is. Having major deposits of these raw materials does not guarantee economic success or survival, nor does the lack of them promise national economic failure, as the case of Japan illustrates so well. Still, these materials are so important that their presence or absence can have great significance for a nation's survival. Extractable Minerals and Mining. Metals are not the only raw materials found in the earth that are economically important. A wide range of minerals and chemicals exist that are valuable, and sometimes irreplaceable, for manufacturing and industrial applications. The more of these a nation has domestically available, the more healthy will be its balance of payments, and the more self-sufficient will it be in times of turmoil among international suppliers or in case of conflict. Energy Resources. Industrialization and modernization have made energy one of the most important commodities. Oil is presently the king of all fuel sources. A country without adequate reserves and resources is forever at the mercy of suppliers and vulnerable to interruptions along the routes the oil must pass. Just having large deposits of oil adds immeasurably to a nation's economic security--though it might also make it an attractive target for a larger, oil-poor country. Coal can be nearly as important, since it can be used in place of oil in many manufacturing and power-generation applications. But other energy resources are important as well. Hydroelectric generation capacity has advantages environmentally and given-- dependable precipitation rates, is both reliable and inexhaustible, within finite limits. Other renewable energy sources are becoming more practical and available as technology improves. Among these are geothermal power potential, solar, and other renewable energy sources. Water resources. Water is one of the most obvious, most crucial, yet most overlooked natural resource. Huge volumes of fresh water are essential for agriculture, industry and domestic use. Good state-of-the-art water management practices can go a long way to offsetting insufficient water supplies. But if in absolute terms there is not enough water, there is no suitable substitute. Agricultural land. Though agriculture itself is discussed above under the economic factor, agriculturally suitable land is a finite natural resource that must be considered under this category. Without adequate farm, forest and grazing land, no matter how well managed, a nation's sustainability is severely degraded and its economic prospects weakened dramatically. With poor management, even a nation with copious agricultural resources can be in serious trouble. Good management, however, can bring even a poorly endowed nation closer to sufficiency. Precious metals and minerals. Though many rare metals and precious and semi-precious minerals have industrial value, these resources are most valuable as a supplement to the national economy--particularly for foreign exchange, as is demonstrated most noticeably by South Africa. Even when burdened by international sanctions, the value of that country's precious mineral and metal resources provided a favorable balance of payments. Marine resources. Many nations depend on products from the sea for a major portion of their food supply and economic resources. Fish, kelp and other sea flora, shellfish and chemicals are all economically important commodities that can be harvested from the ocean. The Socio-demographic Factor Language. As the cases of both Belgium and Switzerland demonstrate, a uniform language is not essential for viability. Yet a common language has significant influence in unifying a people. A language doesn't just communicate verbalized ideas. It's structure and usage carry with it as well an unspoken mental construct that affects the behavior and thought processes of those who habitually use it. Linguistic diversity, on the other hand, is at best a social and cultural complication, and can add to tension and division if there are other conflicts present within a society. Ethnicity. Ethnic homogeneity does not guarantee political and social harmony, nor does ethnic diversity automatically generate conflict. Nevertheless, ethnic differences tend to feed social disruption. If such disruption does occur, it tends to be more severe. Conversely, ethnic uniformity generally promotes more social harmony. Evaluating the ethnic makeup of a country in context with other factors reveals much about a nation's prognosis for survival. Social Fabric/Class Differentiation/Stratification. Too wide a gap between upper, middle, and lower classes, with no promise of upward mobility, can be more socially disruptive than ethnic differences. This is particularly true in many developing countries where there is a vast, severely economically depressed underclass contrasted with a minuscule but highly visible privileged class. Religion. Religion may or may not be a significant factor in national stability, and hence viability. Variables that determine this include the society's own level of tolerance for religion in general, and specifically for religious variety, which then interacts/conflicts with the character of the specific religion or religions involved. Conversely, some nations' policies are highly tolerant of religious differences, such as the US, while others, such as Iran, are highly intolerant. Some religious philosophies are politically and/or socially neutral, while others can be highly disruptive in certain contexts. Much like combining volatile chemicals, some religions do not mix well or safely with others. The resultant interactions can be highly destabilizing, as demonstrated historically during the religious wars in Europe, or today in Northern Ireland. Some protest that the troubles in Ulster have less to do with religion and more to do with the natives' social conditioning; yet religion is intrinsically social, cannot be separated from it, and is intimately involved in what goes on there, paradoxically as both a stabilizing and destabilizing influence. Education and literacy. The level and quality of education within a population profoundly effects the quality and effectiveness of all aspects of the nation. Though educational quality can be improved, it is time- and resource-intensive. Knowing about the educational context of a country can serve as an indicator for two things: the social and economic state of that country, and its prospects for at least the next decade. A poorly educated populace--particularly in today's world--severely weakens a country economically, socially, technologically and militarily. But because people are not computers, to be programmed with new information in a few minutes, it takes years to raise the educational level sufficient for the maintenance of a modern nation-state. National Character and Will. One sometimes must be cautious when discussing National Character to avoid the appearance of bias or racism. The difficulty arises because of the human tendency to evaluate others by one's own standards. It has often been observed that people of the Eastern Hemisphere approach life from an entirely different point of view than do those of the West. The same can be said of differences between the northern and southern hemispheres. Precise, schedule-oriented and literal Westerners often become frustrated or disdainful of those in the Third World who approach life in a less categorical and regimented fashion. Some cultures, on the other hand, might dismiss westerners as being boorish or "over-hasty." Even among related cultures, philosophies, mores and behavior differ, and are valued differently depending on cultural perspective. Ask a Frenchman, an Englishman, an American, and a German about the respective qualities of each national culture and you will discover certain biases, both pronounced and subtle, in favor of each person's own particular national perspective, despite attempts at objectivity. Population density and distribution. In absolute terms, there is probably an optimum range of population densities that ensure the best functioning of a nation and society. A country with too widely dispersed a population would have difficulty mobilizing and effectively developing its resources, infrastructures and social institutions. Too dense a population, on the other hand, breeds crime and psychosis, and can present serious health and economic problems. But with population density, there are no absolutes. Some quite densely settled countries are also highly successful in most or all aspects of nationhood. Japan, of course, is a premier example, as are certain other Asian countries, and the Netherlands. The opposite can be true, though. India, China, and some of the Latin American countries show considerable social strain and deprivation as the result of overpopulation or poorly distributed population densities. Health. Experience, proficiency, and availability of health care professionals, as well as accessibility and sophistication of medical care facilities are important factors in national stability. Disease, malnutrition, injury and chronicly poor health care distract the population from national development and deplete essential human resources. Life expectancy and infant mortality rates are prime indicators of the state of a nation's health care, and reflect its economic and social condition. Quality of life. Economic, educational, cultural, health, social, governmental, and resource issues are among the many variables influencing quality of life. Quality of life in turn is a major component in national stability and political health. A low quality of life can contribute greatly to popular unrest, particularly when people's expectations are raised by comparing one's own local conditions with those of populations in progressive, developed countries or elites in one's own country. The Political Factor Politically Significant Groups and Personalities. Good leadership is essential for national stability, particularly in a nation's formative stages. Historically, any emerging nation has needed larger-than-life, charismatic personalities around whom to rally. Often, the political opposition has fielded equally compelling leadership, creating considerable struggle in the political life of the fledgling nation. This struggle can be good, if it ultimately strengthens the nation. It can also be sufficiently disruptive to destroy any chances for success, particularly if there are other factors weakening the fabric of the nation. Significant elites are also important in the same positive and negative ways. It is from these groups that the leaders emerge, and from which support and political structure develop. Knowing as much as possible about leading personalities and elites can greatly improve analysis of a nation-state's future prospects. Political Cohesion. A certain degree of unity is essential for a nation to survive intact. The Lebanese "civil war" shows us what can happen when the number, power and extremism of political and social factions becomes excessive. Somalia is a further example of rampant factionalism and its impact on national cohesion. Upon the collapse of Barré's government, various warring groups destroyed most of what was left of the national structure, which was replaced by a degenerate feudalism. Not only did this leave Somalia completely at the mercy of any neighboring country inclined to intervene in its affairs, but created a situation which made intervention practically inevitable. Political Tradition and Preferred Governmental Styles. How the populace traditionally relates to politics and government is important. Extremes of either apathy or radicalism can be equally damaging to a nation's stability. A nation's people must have a certain willingness to participate in the political process. This insures ongoing governmental responsiveness to the needs of the populace and lessens the likelihood of corruption or factional co-opting of the reigns of power, or of a coup seizing them outright. Further, the political system adopted by a nation must be appropriate to the level of social development and culture of the people. Bureaucratic Professionalism and Organizational Experience. A country can have the best governmental blueprint possible, yet the government will never function properly if the people who are supposed to run it are not adequate to the task, thus weakening the nation and potentially threatening its survival. The individuals who make up the bureaucracy must not only be competent in administrative procedures, but must also possess at least a minimal sense of allegiance and obligation to the well being of the nation they serve. Professionalism is especially important, since graft and corruption are not only highly contagious, but can undermine stability and spark anger, resentment and radicalism among the population. On the other hand, a corps of professional civil servants can be instrumental in ameliorating the effects of weak national leadership, while making the most of scarce resources in other sectors. Diplomatic clout/foreign affairs experience. Although the focus of this discussion of viability is directed primarily inward, how a nation deals with others in the international sphere can impact greatly on its own survival. This becomes particularly important in a country with limited military resources, which requires skillful use of diplomacy to defuse potential international problems. Security Military geography. Defensible borders are always a security asset. But topography and terrain play other important roles. Should an enemy force penetrate a nation's interior, blocking terrain and defensible land features are important in limiting the depth and strength of the attack. While difficult terrain can be an advantage for the defense in event of an attack, it can serve as a haven for guerrillas and terrorists in low intensity conflict situations. It can also make it proportionately more difficult to rush supplies and reinforcement from one point to another within a country in during a crisis. External threats. Some nations have neighbors that historically pose significant threats. Poland has always had to fear both Germany and Russia. Belgium has always been at the mercy of Germany. Korea and what today is Vietnam have always been threatened by China. Modern times have created or redefined sets of antagonists: India and Pakistan; Iran and Iraq; Syria and Israel. Though especially in the last decade some belligerencies have disappeared, new ones have been created and old ones reignited, it still remains the case that external rivalries can pose significant threats to security, or even a nation's existence. Lebanon, for one, has experienced the reality of this principle through invasion from both Syria and Israel. Internal threats. No nation can completely eradicate every cause for complaint, all inequities, every social distinction or difference, or every revolutionary and radical in its society. There is always some degree of threat from internal dissension and violence. In some societies, social unrest is virtually insignificant and subversive groups nonexistent. In other societies, internal schism, civil unrest, or rival power groups undermine the fabric of the nation, threatening its very existence. The propensity for internal unrest is an indicator of a nation's stability and survivability. Public safety. Only wise public policy and intelligent use of resources can address the problems underlying internal instability and unrest. But it is the responsibility of the public safety apparatus to buy time for implemented solutions to succeed. The first and most important element in public safety is public respect for law and order. Few citizens realize how tenuous is the hold of law enforcement and internal security agencies, even in repressive states. Like the proverbial elephant, conditioned through his life to think the string that in reality binds his ankle to a stake is a heavy chain, a populace bent on anarchy or the destruction of the social system could easily overwhelm any security force ranged against it. Fortunately, in most societies the populace as a whole recognizes the value of civic responsibility and good order. Part of the strategy of an insurgent movement is to undermine public trust in the government and its agencies responsible for maintaining security and public order. If trust is successfully destroyed, the country could be in real danger of disintegration. It is evident then that the sophistication, reliability, loyalty, professionalism and adequacy of police and internal defense forces to deal with internal threats becomes extremely important. Professionalism, reliability and loyalty are perhaps the most important. Political activism, corruption and uneven performance among the police and security forces are virtually certain to destroy public morale and spur the population to question the legitimacy of both social structure and national government. Military. A military establishment is traditionally seen as one of the essential institutions of statehood. A military presence is deemed indispensable to either deter or eliminate external threats, and lend reinforcements in event of internal disaster or civil unrest. A military, however, is at best an uncertain instrument. Particularly in developing nations the military has been as destabilizing as any other element. Instilling true military professionalism can avoid some of these problems, but often even having a military does not prevent the unthinkable from happening, as France discovered in 1940. Sometimes there is no substitute for a strong, capable military, as the United States discovered in World War II. On the other hand, maintaining such an establishment is extremely expensive, and can drain a nation's economy, in itself a serious threat to survival, as the Soviet Union discovered at the end of the Cold War. Japan has reaped the advantages of low defense expenditures. And Costa Rica to the present has fared very well with no military establishment whatsoever. Having or not having a military can thus be a plus or minus for viability depending on circumstances. In the end, however, a nation must with few exceptions have either a military or an alternative security arrangement adequate to protect it from external threats. Security partnerships. Few nations exist with no external threats, so those lacking a military must have some alternative means of protection against attack or unwelcome pressure from other international actors. Japan enjoys the protection of the United States, but of even more significance is the case of Taiwan. Without the US guaranteeing the island nation's sovereignty, it would certainly by now have been occupied by the Peoples Republic of China. Without these same guarantees, North Korea would have attacked, and probably defeated, South Korea long ago. In the absence of a significant military establishment, the existence of a suitable alternative means of maintaining security against external threats is imperative. These alternatives might take the form of alliances, mutual support pacts, etc. INTERRELATIONSHIPSHaving established basics for the viability factors and their sub-factors, it becomes important to understand not just the factors themselves, but also the relationships between them. The political is, for example, intertwined with the socio-demographic. Education, ethnic and class distinctions, and even religion are all factors related to society or demography, yet each can have significant political and/or economic impact as well. The picture is equally complex and interrelated when one considers factors overlapping both demographic and economic categories, as, for example, employment and work force. Ingredients such as resource distribution, available lines of communications and transportation--not to mention accessibility to external lines of trade--though directly relevant economically, are also influenced by geography, while the presence or absence of blocking terrain within a country or along its borders transcends a mere geographical or economic importance to play a leading role in the security aspects of a nation's viability. Even the nature and degree of a people's national identity, sense of self-reliance, and willingness to make commitments and sacrifices to guarantee the existence of their nation-state play an essential role in the concept of security--but also have great significance politically and economically. Security factors--whether involving internal or external security--in turn connect with all other categories, in that they provide, when present, the sound foundations necessary for the conduct of the business of society; when absent, they guarantee the virtual still-birth of a nation-state. ANALYTICAL EVALUATIONHaving established the components of viability, it is now possible to fabricate some rudimentary tools with which a nation's relative potential for viability can be assessed. We will portray each sub-factor as a continuum with a value somewhere between 0 and 10 according to its degree present. Each of the factors can then be evaluated for a given nation--Palestine, for instance. Of course, when dealing with an existing country, the process of establishing the scores for each of the factors will involve a certain amount of subjectivity. However, research, analysis, and comparison will hopefully provide a body of facts to improve the accuracy of these "educated guesses." An approach that could improve the evaluation process's objectivity might be to have several acknowledged experts independently evaluate all available information and provide scores for each category within their areas of expertise. These scores could then be tabulated and averaged, providing a consensus score for each sub-factor. Unfortunately, this approach is beyond the resources and scope of the present paper, but could perhaps be attempted in the future. Assigning values against the various viability factors provides certain advantages. We could take other nations, evaluate them for these same factors, then establish graphic profiles to compare against our ideal model and against each other. Particularly, we can explore in detail the viability factors for Palestine, create a profile, and compare it other countries which we know to be viable. This could give us at least a general idea as to the true potential for survival Palestine would have. We can also derive a very general "viability coefficient" by averaging all the scores for the sub-factors under each of the factors, adding each of these averages, then dividing the resulting total into 6, the total number of factors. At the end of this process, an ideally-viable country, for example, would have a viability coefficient of 1.0. Real-world nations would have coefficients less than 1.0: i.e., .96, .43, .77, etc. Using a coefficient provides an even simpler tool for comparing national viability than does comparing graphs. If, for example, several very stable, well-established nations were to have viability coefficients ranging from, say .63 to .89, while other, less stabilized, somewhat dysfunctional countries had coefficients ranging from .33 to .63, we would suspect that if Palestine were to manifest a viability coefficient of .18, .27, or .31, it's prospects for survival might reasonably be questioned. If, on the other hand, it were to manifest a more robust coefficient of .51 or .83, its potential for viability might give reason for hope. A Note to the Reader on Methodology To be sure, this continuum/coefficient scoring concept has several drawbacks. The first is the inherent subjectivity. Since precise, empirical data cannot be identified for most factors--what scientifically measurable score, for example, could be determined for "national character"?--personal judgement of the analyst or researcher is unavoidable. Secondly, it is impossible to weight the factors or subfactors for greater or lesser importance. Is, after all, an ethnically-homogenous society more important than presence of smelterable ores? Are defensible borders of greater influence in viability questions than is bureaucratic experience? Will an extensive, navigable waterway be more significant than religious factionalism? Not only are such questions essentially unanswerable, but their relative importance probably changes from country to country according to circumstances. The methodology employed in this thesis is clearly unconventional, meant to be creative, and is obviously not a usual technique employed in the behavioral sciences. This approach has been used to allow a more flexible analysis of a difficult question where it would be otherwise extremely difficult to arrive at even tentative conclusions due to the near impossibility of securing reliably empirical data. As would any researcher, I have reservations about the approach. But this material is the product of research and significant analysis of the region and parties to the conflict, the result of a review of many previous studies on the politics and issues of the Palestine Question, and as a result constitutes more an "informed judgement" rather than arbitrary opinion. For the reader who has concerns about the subjectivity of the method, I too share those same reservations. However, to complete a study which is clearly unique and without precedent, it is necessary to take methodological liberties in generating the information that follows. TABLE 1: COMPARISON OF ELEMENTS OF NATIONAL POWER

NOTES

Frederick H. Hartmann, The Relations of Nations, (New York: Macmillan), 21. Karl W. Deutsch, Nationalism and Social Communication, (New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1953), 70. Deutsch, 71. Deutsch, 73. Deutsch, 75. Deutsch, 79. John Stuart Mill, "Considerations on Representative Government," quoted in Hartmann, 21. Hartmann, 30. Ann Mosely Lesch, Transition to Palestinian Self Government: Practical Steps Toward Israeli-Palestinian Peace, (Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, 1992), 19. Ray S. Cline, World Power Assessment: A Calculation of Strategic Drift (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic Studies, 1975). Hans J. Morgenthau, Politics Among Nations, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf), 1978, 117-155. Hartmann, 45ff. Werner J. Feld, International Relations: A Transnational Approach, (Sherman Oaks, CA: Alfred Publishing Co.), 1979, 31. David N. Farnsworth, International Relations: An Introduction, (Chicago: Nelson-Hall, 1988), 41-57. Morgenthau, 129. Hartmann, 49. Hartmann, 53. Morgenthau, 137. Morgenthau, 130. Morgenthau, 151.

|