HOME DUST JACKET REVIEWS CHAPTER 1 CORRECTIONS PRESS RELEASE ORDER the BOOK |

ASSESSING THE VIABILITY OF A PALESTINIAN STATEIn some sociological and demographic respects, Palestine will have an easy adjustment. There will be other areas, though, that will serve to greatly complicate the emergence of a Palestinian state. LANGUAGE Palestinians speak Arabic virtually universally. Differences in dialect are insignificant. Uniformity of language will contribute to the potential for success of the State of Palestine. ETHNICITY Ninety-eight percent of the population of Palestine is comprised of Palestinian Arabs, though there are a few minor ethnic groups native to the area. Overall, ethnic homogeneity will be a positive element in the future of Palestine. SOCIAL FABRIC/CLASS DIFFERENTIATION/STRATIFICATION Social structure and class present a somewhat more complicated picture for Palestine. Traditionally, there were simple but profound divisions. The wealthy merchant and landowning families, the so-called "Notables," represented the pinnacle of Palestinian society. The vast majority of the Palestinian population was relatively poor tenant farmers. Whatever bourgeoisie class existed was tiny and uninfluential. Huge changes occurred in the Palestinian social structure, as Arab nationalism grew, Jewish settlement increased, the Turkish empire disintegrated and was finally dismantled, Britain and France administered their resulting mandates, new Middle Eastern nations were formed, the State of Israel was founded, and major wars were fought between the Arabs and Israel. Large numbers of the peasant class were displaced, literacy increased, urbanization trends escalated, and a large body of displaced Palestinians was created--living both externally throughout the Middle East and the West, and in camps within the occupied territories, Jordan, and Lebanon. The Palestinian upper class, which had always "functioned as an interlocutor between government and governed," 1 lost power in a matter of a few decades. After the June 1967 war, its influence eroded rapidly. This stemmed partially from the fact that many of the Notables' sons were abroad at western academic institutions during the Israeli takeover, and could not return to inherit their fathers' roles and influence in the community. More compelling, however, was the loss of economic power the Notables suffered as they surrendered land to Israeli expropriation, and lost laborers to jobs in Israel or abroad. Also significant in the Notable's decline was the loss of respect from and influence among the Palestinian masses it suffered due to its inability to halt or slow the Israeli settlement of the West Bank, and because of its perceived collaboration with the military government. 2 In its place a leadership class has developed that is "younger and much less identified with the notable families of Palestinian society," often representing "Palestinians of the refugee camps and of the urban working class." 3 It is more politicized, populist, and independent. One consequence has been a "generational cleavage," originally created by "the experiences of the young in seeing liberated, mobile Israeli youth." In some areas this generation gap had been somewhat lessened by intelligent leadership, but in others it was exacerbated by inflexibility and traditionalist thinking among the Palestinian social and political leadership. 4 This cleavage has been greatly aggravated by the intifada experience. "Youths in their teens and twenties played the vanguard role," according to Don Peretz. They serve "not only as foot soldiers, but [as] leaders of the intifada." Since many of them come from the lower classes, from the villages and the camps, they bequeath a much more populist flavor to the uprising. 5 But they also contribute an anarchistic element to Palestinian society.

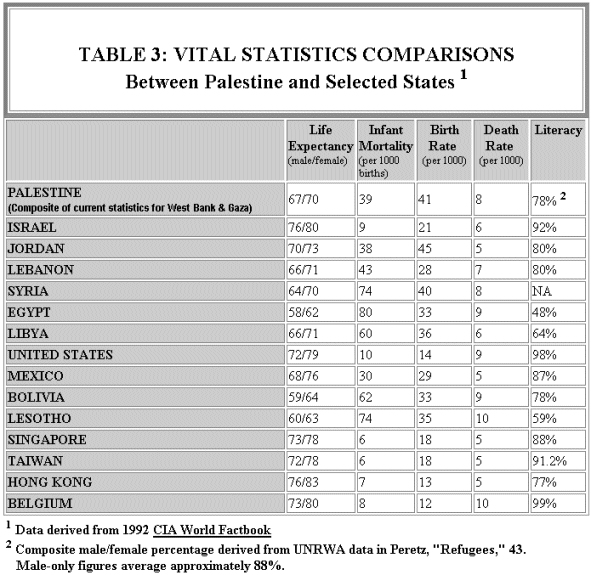

RELIGION On the surface, religion would seem not to be a major issue for Palestine. An overwhelming majority of all Palestinians are Moslems. Of these, 95% are Sunni Moslems. The relatively small numbers of Christians--which make up about 15% of the Arabs in the West Bank--live in general harmony with the Moslem majority. However, there is a strong resurgence in fundamentalist Islam that potentially could cause rifts in the social fabric of a future Palestinian state. Some of the most significant effects of this will be political, and will be discussed later under the Political Factor. The current revival of Islamic fundamentalism is a recent development, beginning its resurgence in the 1970's, and epitomized by Khomeini's takeover--and makeover--of Iran in 1979. Since then, it has gradually been making inroads throughout many Mid-East Moslem nations. At first, the Palestinian movement, with its focus on the secular PLO and the guerilla war, seemed relatively immune to Moslem fundamentalism. Fundamentalism could nevertheless be found among the Palestinians in embryonic form. As a result of the PLO's banishment to Tunis and the clear powerlessness of the surrounding Arab countries to succor the Palestinian cause, Palestinians began to turn increasingly toward fundamentalism as an outlet for their frustrations during the early-to-mid Eighties. With the intifada, Islamic influence began to rise. Using daily reading of religious literature as an indicator of potential fundamentalist leanings, a study published in 1989 estimated that about 20% of those Palestinians surveyed were likely to be sympathetic to fundamentalism. Over the preceding five years, the survey found that 10.7% of adults aged 25 to 30 had increased their reading of such literature. Another 6.3% had decreased its reading. Based on these findings and others, the study concluded that the rate of increase of fundamentalist sympathies was nearly twice that of the trend towards secularization. Despite the trend, the vast majority of the Palestinian people remained uncommitted to either approach. 11 Over the past several years many experts have warned that increasing repression by the Israelis, coupled with mounting frustration with Israeli economic and settlement policies would both drive more people into the fundamentalist camp and increase in degree of desperation the acts committed by Islamic activists. "Increasing support for Islamic fundamentalist factions among the Palestinians . . . is an indication of frustration with the impasse," which is demonstrated by Hamas' increasing strength and the growing occurrences of fundamentalist cooperation with "militant factions within the PLO which reject any form of political compromise." 12 (Washington, DC: Defense Intelligence College, Nov. 1992), 9. Other researchers warn that--though previous studies found that the secular nationalist movement was "overwhelmingly supported"--if the nationalist struggle fails to show concrete progress "support [could be expected] to be transferred to the Islamic fundamentalist movement," which would likely "shift its strategy to armed struggle and violent confrontation." 13 The increase in lethal violence perpetrated by Islamic fundamentalists against Israeli settlers and territorial officials beginning in the fall of 1992 shows these concerns to be prescient. The growth in fundamentalism poses increased problems for the fabric of Palestinian society, since it brings with it increasing confrontation with the secular movement. "Though the change toward religiosity and fundamentalism was almost twice as great as their competing currents," secularism remains strongly entrenched, making conflict virtually inevitable. In the early 1980's university students from usually competing power blocs created a coalition opposing the Islamic movement, calling it "reactionary" and "destructive." 14 By 1990, "interfactional fighting between the secular-nationalist groups and the Islamic fundamentalists" became "perhaps the greatest source of demoralization" for Palestinians in Gaza. Indeed, violent confrontations have erupted, in one instance so distressing the people of the community that to halt the fighting they physically intervened against both the religious and secular factions involved. Islamicist tactics upset many unaligned and secularist Palestinians. For example, in Gaza, where fundamentalism is more entrenched, members of Hamas have reportedly attacked with vegetable dye women deemed "inappropriately attired," creating resentment and sparking angry reactions. 15 In light of such confrontations and the growing power of the fundamentalist movement, the potential for a major inter-communal struggle between religious and secular factions once Palestinians have a state of their own may be great. The primary issue, which is already endemic and could escalate during the nation-creating process, would be the nature of the state itself--would it be secular or religious? An equally serious question would be what the relationship of Palestine to Israel should be--could the state give up any notion of having a literal claim on the whole of historical Palestine, and coexist peacefully with the Jewish state? Or would the religious imperative strive toward uniting all of the land west of the Jordan under one Islamic banner? The very nature of the controversy would make a compromise solution difficult. While secular approaches (with Marxism a possible exception) tend to be open to compromise, absolutist religious views--especially on the part of the more ardent fundamentalists--could make things very sticky indeed. It is possible that serious societal conflict could arise, resulting in the extreme case of a traumatic civil war that would directly threaten the survival of the Palestinian state. There are two factors that may work to mitigate the religious-secular dichotomy. First is the nature of the growing support for fundamentalism in the first place. Since many Palestinians-- frustrated at the lack of progress towards accomplishing their nationalist goals--appear to be gathering under the fundamentalist banner "because they [can] see no other solution to their plight," 16 there is great likelihood that they will moderate their zeal and gravitate back toward secularism once their goals are achieved. In such an event, religious fundamentalism would by no means disappear, but it would become far less influential in the political and social life of Palestine. A second modifying factor would be a possible moderating trend in fundamentalism. As one expert points out, "not all Muslim religious leaders oppose peace negotiations and not all fundamentalists" are rejectionists. 17 Another observer notes that one group, the Muslim Brotherhood (out of which Hamas originally grew) has had "broad success in recent years building a nonviolent Islamic political movement willing to work within Israel's democratic political system." 18 If this sort of approach is continued by this and other groups inside Palestine, a workable secular-religious pluralism might be achieved. EDUCATION AND LITERACY For decades, the Palestinian people have been widely respected for their educational and academic accomplishments. "Palestinians long had a reputation for putting a premium on education. . .They competed with the best students at Jordanian and Egyptian universities," observed an educator in a West Bank university. 19 Many gained the respect of their peers as they earned advanced degrees in the West. Their educational credentials often qualified Palestinians for important, often influential, and sometimes even prominent positions in business, science, academé, and government in the Middle East, and on occasion in Europe and America. 20 Education was seen as a ticket out of the frustrating and oppressive situation in which many Palestinian families found themselves--and so it proved to be for many. "Without land, [Palestinians] have only education as a capital asset." 21 But as a consequence of the intifada and the Israeli response to it, the Palestinian educational edge in the territories is being blunted. Beginning in 1988, schools throughout the occupied territories have often been closed, often for periods running to several months. Though the Israelis may still close schools in reaction to demonstrations or riots, primary and secondary schools have been reopening sporadically since 1989. Colleges and universities, however, only began reopening in 1992. Schooling in the territories had already suffered over the years from the policies and neglect of the Israeli military government. 22 As a further result of the missing months and years of school, literacy, knowledge base, and study skills of Palestinian students have severely declined. Children and young adults who have been at the forefront of demonstrations and confrontations with Israeli troops, and seen their family structures erode as a result of the intifada, have lost respect for teachers' authority. And the school infrastructure has suffered equally. Buildings have deteriorated, new buildings have not been erected to cope with the growing student-age population, and facilities, equipment, and textbooks have fallen into disrepair and obsolescence. Presently there are slightly more than 1320 schools in the territories. This figure includes government, UNRWA, and private schools (UNRWA maintains almost 400 more in surrounding countries). Student-to-teacher ratios average 37 for elementary grades, 15 for preparatory, and 18 for secondary, though ratios vary greatly from area to area, the highest being in the Gaza area, where elementary grade ratios reach 42-to-1. 23 (One source reports teacher-to-student ratios in Gaza of 50-to-one. 24) There are 25 community colleges, 21 of which are accredited, and six universities. University students number about 14,500. Of the 830 professors and instructors, 86% have postgraduate degrees. 25 Many Palestinians have chosen teaching as a career, and have gained considerable experience in positions throughout the region. Unfortunately, many teachers in the territories are "underqualified, lack teacher training qualification, and are generally underpaid." 26 Though the intifada grinds on, there is escalating concern among Palestinian parents and leaders about the educational situation. "They see school curricula and study habits shattered," leaving behind young adults who are struggling to catch up to where they were, let alone prepare themselves for future jobs or compete in college classrooms." So bad was the situation in 1989 that large numbers of students, desperate after falling so far behind, engaged to a disturbing degree in cheating on the tawjihi, the annual examination crucial for advancement. 27 Having an entire generation of students who are as much as five years behind in their education represents a huge deficit for Palestine's human resources. The picture is, however, not altogether bleak. Even during school closures, for example, UNRWA kept teachers on full salary to promote as much as possible the schools' quick recovery whenever they reopened. 28 Teachers in the territories also tried the best they could to provide alternative schooling, though such measures usually met with mixed results at best. And, once again, education is coming to be seen as the gateway to escape powerless and indigent circumstances--the primary "capital assets" to which Palestinians have access. Teachers, leaders, and parents are working to slowly correct the situation. The intifada leadership has taken steps to restore the education system, by decreeing that students and teachers be exempted from participating in general strikes 29, and by demanding that factional rivalries and men wearing masks stay away from schools. 30 And there remains a well-educated strata among adult Palestinians. Regrettable as it was, the mass expulsions from Kuwait after the Gulf War brought an influx of many experienced and literate Palestinians into Jordan, half of whom had university degrees. 31 If these resources sometime soon become accessible to the State of Palestine, they will be invaluable. NATIONAL CHARACTER AND WILL A people's native motivation and determination play an extremely important role in the success of the nation to which they belong. Though unmeasurable by standard instruments, there are indicators that can give us an idea as to the presence and depth of these important qualities. Some of these indicators include endurance under adversity; individual willingness to sacrifice for the corporate good; innovative solutions for surmounting obstacles; communal cooperation; and perseverance against opposition. If these qualities are not present originally, they may often be brought out by challenges and trials that are uniformly imposed upon most or all of a people either by unfortunate circumstance (drought, famine, earthquake) or by an outside human agency (aggression, oppression, suppression). These qualities exist among the Palestinian people. Perhaps the intifada is the best example of this. The spontaneity and universality demonstrated at the very beginning showed plainly the thoroughly-grassroots basis from which the intifada arose. That the intifada continues despite imaginative, and sometimes almost drachonian Israeli countermeasures shows an amazing strength of resolve. The spirit of cooperation practiced by merchants, students, workers, teachers, women, farmers--all the different segments of the Palestinian community--in supporting the intifada's leadership in strikes, demonstrations, and coping strategies is a further demonstration of Palestinian determination. These coping strategies themselves are evidence of innovative attempts by the Palestinians to overcome obstacles or solve problems caused by punitive withdrawal of services and support originally provided by the military government. By developing and implementing these strategies--growing vegetables in one's front yard, conducting classes in mosques when schools are closed, or attempting to replace Israel-produced goods with indigenous ones--the effect of Israeli countermeasures can at least be alleviated, and sometimes even negated. Though the "overall effect of these measures is probably more psychological than economic," they are far more important for the effect they have in increasing morale and national consciousness. 32 The very concept of sumud--"steadfastness," or "solidarity"--in the face of the occupation, implies character and strength of will. It implies a growing sentiment of "we must all hang together, or we shall hang separately." The intifada is not the only evidence of the strength of Palestinian character and will. The fact that the PLO continues to exist, despite the rampant factionalism within the Palestinian's own ranks and attacks by Israel and various Middle Eastern governments testifies to the determination that underlies the Palestinian movement, despite its internal differences. Even the notorious, often ruthless guerilla operations of the PLO and other radical Palestinian groups bears testimony at least to this determination. Of course, one might ask whether Palestinian steadfastness developed because of national character and will, or whether character and will developed as the Palestinian people confronted challenges, dangers, and perceived subjugation. In the end, the answer to this question doesn't really matter--the end result is fundamentally the same. It is ironic that the hardships the Palestinians endure because of deliberate Israeli attempts to stifle national identity may instead actually serve to reinforce it. The very attempts to quash Palestinian identity and independence seems to create a "refining fire" that anneals and tempers the Palestinian identity so that it can withstand the rigors of the birth and the development of its own nation-state. POPULATION DENSITY AND DISTRIBUTION Density A possibly serious socio-demographic problem is the sheer size of the potential Palestinian population in proportion to available land. Thanks to the numbers of Palestinians leaving the occupied territories in past years in search of greater opportunity and better jobs elsewhere in the Middle East, Europe, and the United States, the population of the West Bank and Gaza had not increased anywhere near the rate that might be expected given the chronically high Palestinian birthrate. Nevertheless, based on today's estimated population for both West Bank and Gaza of approximately 2.265 million, 33 and given a state that included the approximate area of the West Bank and Gaza (6020 square kilometers 34), Palestine's population density would reach about 376 people per square kilometer. Once a state is founded, however, many Palestinians in the diaspora would likely return almost immediately. Estimates range to as many as 750,000 Palestinians abroad that might return to the new nation, rapidly making conditions more cramped, with densities of about 500/km2. 35 In the unlikely event that most, or even all of the expatriate Palestinians were to return, the population would certainly exceed four million, creating a density approaching 660 persons per km2. For comparison, population density in Israel is 233 per square kilometer; in Japan it is 329/km2; in the US it is just over 27/km2. 36 While other places sometimes thrive with high population concentrations (the Netherlands, at 405/km2; Hong Kong, at an incredible 5949/km2), such places are inevitably blessed with a highly fortuitous location and/or far better and more available resources. Distribution The densest population in Palestine is in the Gaza strip area (approximately 2034 people/km2). The balance of the population occupies the western-most two-thirds of the West Bank. Four "urban centers" are the focus of Palestinian population: Jerusalem, Nablus, Hebron, and Gaza. Nine major towns, among them Bethlehem, Jenin, and Jericho complement the larger cities. There are a number of suburban communities, and numerous rural and semi-rural villages and towns. Except for the relatively more difficult terrain above the Jordan valley and bordering the Dead Sea, settlement patterns are fairly uniform. With the establishment of Palestine, a program would have to be instituted to both alleviate the seriously overcrowded conditions in Gaza and some of the more congested urban areas, and to intelligently provide for the re-settlement of expatriate Palestinians returning to the new state. Properly managed, this program could maximize the integration and use of the country's human resources, and minimize the negative effects of a densely-settled population. High population densities are not necessarily a threat to a nation's viability. Much depends on the infrastructure, political organization, and economic circumstances of the country. In fact, modern development requires population concentrations to facilitate business and industrial production. High population densities are most problematic in countries that rely heavily on agriculture--the large areas required for dwelling places, roads, and public and private facilities can seriously encroach upon productive agricultural land, and make heavy demands on limited water supplies. One of Palestine's few natural resources is its farm, orchard, and pasture lands. These are particularly valuable resources in a region in which such things are otherwise in short supply. Presently, there remains marginal and unproductive land that might be used for settlement. Still, population growth and distribution will need to be managed to insure valuable resources are not destroyed just to find room for everyone. HEALTH While overall health among Palestinians has improved over the years, it still lags behind developed nations. Current life expectancy is somewhat lower than neighbors Israel and Jordan, but is slightly better than that of Syria and about the same as Lebanon's (see Table 3 for comparative numbers). The moderately high Palestinian birth rate is only slightly offset by a high infant mortality rate. Life expectancy in Gaza is slightly lower than in the West Bank, while birth and infant mortality rates are somewhat higher, as would be expected in the more congested, less developed environment. 37 Healthcare is complicated by the fact that only 34% of Palestinians are covered by insurance, and many of those not covered have no access to medical care because of the expense. Distribution of facilities is also problematic, with one 1988 study reporting that 56% of population centers in the West Bank have no local health centers, and 57% have no maternal and child health clinics. All in all, the same study concluded that the Palestinian healthcare system "suffer[ed] from shortage in manpower, material and equipment resources." 38 There are many maladies and health deficiencies that will disappear once the system is adequately expanded and resourced. Yet, despite its shortcomings, Palestine's health profile puts it moderately better off than most Third World and developing nations, if worse than most industrialized Western ones.

Palestine has an extensive recent tradition of concern about healthcare, and the beginnings of a healthcare infrastructure that, if it is oftentimes inadequate for the population it presently serves, can at least act as a jumping-off point for the development of a well-established and competent system. Three elements form the foundation to Palestinian health care: the Palestine Red Crescent Society, UNRWA medical infrastructure, and health services within the territories.

QUALITY OF LIFE Precisely defining quality of life is difficult, perhaps impossible. As mentioned in the opening chapter on the Factors of Viability, it is a blend of all the elements of a society, from education and healthcare to cultural events and adequate employment opportunities. The fact that it defies precise definition does not mean, however, that it is not an important element in the survivability of a nation. Two factors are important with regard to the concept of "Quality of Life"--perception and reality. Of these, perception is the most significant. How a nation is affected by its quality of life is directly related to the population's perception of how good life is or is not. If a population with relatively poor quality of life is unaware that it is possible to have better, the population will accept life as experienced. If, on the other hand, a population with a relatively good quality of life in absolute terms has the perception that the quality of life is inadequate, and can and should be improved, the population will be restive, demanding, perhaps unruly or even disruptive. Reality--as represented by quality of life as it really is, rather than as it is perceived to be--is only important when one society or culture butts up against another and there is opportunity for comparison. It is at this point where have-nots discover that they, by their lights, are being short-changed, and dissatisfaction begins. While dissatisfaction with quality of life seldom in itself brings about a nation's collapse, it can be the catalyst that sparks a chain of events that can bring collapse as a result. In Palestine's case, rising and falling expectations will play a significant role in the inner stress and turmoil of the state. Just by living in close proximity to cosmopolitan Israel, the expectations of Palestinian youth have been raised dramatically. They see the consumer goods, the freedom, and the opportunities their Israeli counterparts enjoy, and are frustrated--not only that they don't enjoy similar advantages, but that there is no hope that they will enjoy them. These frustrations certainly played a role in the spontaneity of the intifada, and probably are an element in the increasing flirtation with Moslem extremism and violence currently taking place in the territories. The State of Palestine will have an instant built-in advantage when it comes to quality of life perception. Just the mere fact of its creation, bringing with it the lifting of onerous restrictions imposed by the military government, will cause an immediate impression of dramatically improved quality of life. If Palestine takes immediate steps to follow up with progressive initiatives to build the state politically, economically, and socially, quality of life will continue to improve. The development programs initiated by the Palestinians themselves and through aid from other nations will continue to improve conditions. As long as quality of life is perceived to be improving in a reasonable fashion, much social turmoil can be avoided. In the end, Palestine will necessarily pass through a transition time of turmoil and social disruption. But the socially corrosive forces created by the intifada, Israeli occupation, and diaspora may be the very factors that make it possible for Palestine to become a successful, modern state. In order for it to survive, it will have to both integrate and compete economically, politically, and socially with the greater world community. Too strong an influence of the traditional and archaic could be life-threatening to the state. The upheaval and social re-ordering through which Palestinians have and will continue to pass may be the catalyst that allows the transformation into a viable, survivable nation. ASSESSMENT

NOTES

|