HOME DUST JACKET REVIEWS CHAPTER 1 CORRECTIONS PRESS RELEASE ORDER the BOOK |

ASSESSING THE VIABILITY OF A PALESTINIAN STATEAvi Plascov believed that "the question of whether or not [Palestine] would be economically viable is not all that important," largely because any political solution would necessarily have economic solutions guaranteed by the nations of the world. 1 Certainly, if the rest of the world were truly committed to resolving the problem by creating a Palestinian state, part of the solution would likely involve heavy economic and financial support. This backing would continue as long as international interest in supporting Palestine remained high. Unfortunately, when an international problem has finally been resolved, world attention typically wanes as the years go on and other, more pressing or spectacular crises and events occur. Should things so unfold, Palestine's intrinsic economic viability will ultimately be put to the test. For this discussion, the question of economic viability does not revolve so much around how the mechanics of Palestine's economic system would work, as whether the necessary ingredients exist to allow a viable economy, in whatever form, to be set up and operated. WORK FORCE/LABOR POOL In recent decades Palestine has confronted a paradox: lack of sufficient employment opportunities to keep its workers occupied; but not enough workers of the right kind to support economic development for a new state. Under Israeli occupation after the 1967 War, most Palestinians coming into the workforce have been primarily faced with two options--either work as unskilled or semi-skilled laborers in Israeli settlements or Israel itself, or emigrate to countries such as Kuwait, where their education and skills could be put to good use. Israeli policies were the primary controlling mechanism for the Territories' economy, abetting some activities and suppressing others, depending on how various enterprises impinged on Israel's economy or security policies. Consequently, those commercial, agricultural, and industrial activities in the territories that demonstrated any growth at all showed only minor gains. The relatively slow increase in available jobs was far under what was really necessary to keep up with the increasingly large numbers of Palestinians seeking employment. The oversupply of workers proved a boon to Israel, since less qualified Palestinians or those unwilling to leave their homes and families were available to perform the more menial labor that Israeli citizens deigned to accept. Vivian Bull notes that economic development in general, and industrial development in particular were hampered in the 1970's due to a shortage of both skilled and unskilled labor in the West Bank. This shortage occurred largely because of the great demand within Israel for labor in agricultural, construction, and other industries, and because the higher wages in Israel made employment there far more attractive to Palestinian workers. 2 As George Abed observes, from the beginning of the occupation to 1990 the number of workers employed indigenously in the Territories remained stagnant in the neighborhood of 155,000, while the number working in Israel had reached 130,000 by the beginning of the intifada. 3 Many of the more qualified Palestinians simply left. The money these expatriates sent back to families left behind in the territories helped improve the standard of living, but did little to establish a sustainable economic base, since Israeli policies toward development in the territories limited the scope, scale, and type of commercial activities that could be pursued. Had any genuine attempt at development indeed been undertaken, it ironically would have been seriously hindered by a shortfall in the type of workers and managers necessary to sustain growth, since many of the best and brightest of the Palestinian workforce were abroad. The "substantial emigration by some of the potentially most productive elements of the labor force," Abed notes, "deprived the occupied territories of a key factor in its social and economic development." 4 In recent years, two inexorable trends have converged which, though they have caused Palestinians many hardships, have also created an opportunity that could well prove fortuitous, if it coincides with the formation of a Palestinian state. The first of these trends is the ongoing economic stagnation and depression in oil-producing nations of the Middle East. This has had two effects. First, it has dramatically lowered the level of money being remitted by Palestinian expatriates to their families back home, impacting greatly on standards of living and cash flow in the territories and among Palestinians in nearby Jordan; second, it has created extensive unemployment among the expatriate Palestinians. Those unable to find work have in many cases been forced to return to Jordan or the territories, lessening income, aggravating social burdens, and increasing competition for the already insufficient number of available positions. The second factor is the Palestinians' treatment after the Gulf War. Thousands have been expelled from Kuwait and have been treated with increasing distrust in other nations previously hospitable towards Palestinians. Adding to this is the declining opportunity for employment among the Israelis. During the Gulf War Israel closed its borders with the occupied territories, abruptly separating a large portion of Palestinian workers from their jobs. After the borders were reopened a few months later, fewer than 50% of those previously working in Israel still had employment there, and black market jobs where Palestinians unable to find employment elsewhere could at least work for below minimum wage all but dried up. 5 Growing automation and continuing immigration of Soviet Jews into Israel have made inroads in the employment sector dominated until now by Palestinian workers. The Israeli sealing-off of the Occupied Territories in the spring of 1993 aggravated the situation still further. The immediate result of these various developments has been a great deal of social upheaval and considerable suffering on the part of many. But one potentially valuable advantage is that it has created a large pool of available, experienced, educated, and willing (even desperate) workers and professionals with nowhere else to go which could be used to good advantage in building and manning the infrastructure of a Palestinian state--as long as the wait is not too long. Unfortunately, in the near term they cannot be used in developing Palestine's economy. If the peace negotiations presently underway bear fruit, however, and the beginnings of Palestinian autonomy or even statehood begin to sprout, these human resources may begin to be integrated in building Palestine's economic foundations. The occupation, however, has taken its toll on the quality of the workforce within the territories. "There has. . .been a general 'de-skilling' of Palestinian manpower under occupation," caused by "the high demand for unskilled workers in Israel, combined with the security-related exclusion of non-Jewish workers from the highly skilled and professional jobs," along with a certain amount of racism and discrimination. This has been aggravated by a "serious deterioration of. . .educational and manpower development infrastructure," which despite Palestinian efforts to improve the educational system, nevertheless resulted in a decline in educational standards and stagnation in vocational and technical training. 6 Yet there are many positive qualities to be found as well. An important characteristic of Palestinian workers is that they are industrious--they are willing to work, and they work hard when given the opportunity. Many are also ambitious, as is attested by the number of commercial and entrepreneurial enterprises with which Palestinians are involved in the Middle East and elsewhere in the world. Also, despite the problems noted above, Palestinians remain among the most highly educated groups in the Middle East, with a high proportion of college graduates among them. More importantly, they value education and seek it whenever possible. Because of these qualities, until recently Palestinians were often hired to set up and run many important concerns throughout the region. Due to the impact of the intifada on educational institutions, however, educational shortfalls among certain age groups of Palestinians in the territories are likely. Palestinian leaders recognize this problem, and efforts are being made to cope with this deficit. How successfully this problem can be overcome remains to be seen. INDUSTRIAL BASE AND CONSTRUCTION. Industry Heavy industry in Palestine is virtually non-existent. Light and medium industry is represented by extractive activities, primarily stone and aggregate quarrying, and manufacturing and processing industries. Most prominent among the latter is clothing and textile manufacturing, which employs roughly 37% of all Palestinians working in domestic industry. Food, beverage, and tobacco production, which includes such agro-industrial activities as dairy products processing and olive presses, are also important. Other significant industrial enterprises include stone cutting and polishing, glass and ceramic manufacture, metal fabrication (furniture, construction components, machined parts), and a small plastics and chemicals industry. 7 Altogether, industry employs (1988 figures) roughly 19,000 (out of a territorial population of more than two million), or approximately 16%, of Palestinians working in the territories. 8 It becomes apparent how dormant industry has been when we contrast these figures with earlier statistics. In 1965, before the Six Day War, industry employed 15,000 workers and produced seven percent of the gross national product. The war brought about a significant decrease, to 9,000 employed, which increased only to 14,000 in 1975. 9 By 1983, it had inched up to 16,000. 10 Several factors play a role in keeping the brakes on the industrial sector. Reduced consumer demand (at first brought about at least partially by wide availability of Israeli-produced consumer goods, and more recently by economic hardships resulting from the intifada) and riskiness of capital investment were partly to blame. Competition with Israel's comparatively robust economy, the restrictive financial environment, political unrest, and oppressive Israeli policies toward development in the territories were to a greater or lesser degree also significant suppressive factors. 11 Once statehood becomes reality, many circumstances will change. On the negative side, it is possible that the Israeli market, limited as it is for Palestinian goods, will become altogether unavailable. This may be offset by less restrictive access to the Arab world and Europe. Further, industrial development originally made off-limits to Palestinians by the territorial government will be opened up to Palestinian entrepreneurs. Restrictive financial policies will necessarily be abandoned. The need for a wide variety of new indigenously-based industries will provide a broad menu of attractive investment opportunities which, presuming a well-managed infusion of external aid and capital investment, could easily fuel significant growth in manufacturing and industry. Manufacturing of consumer goods, machinery, vehicles, and electronics are feasible for development in Palestine. Many of these may be outgrowths of industrial applications introduced in support of the inevitable expansion in infrastructure. And with Palestine's limited natural resources and potentially large unskilled-to-highly-educated labor pool, industrial production aimed at the export market is a logical direction in which to focus. Assuming an intelligent infusion of capital, enlightened management, and a benign regulatory atmosphere, Palestine has considerable potential for major industrial expansion. Construction Where industry currently represents only 7.7 percent of the West Bank's gross domestic product (GDP), and 13.7% in Gaza, construction provides 16.8% and 21.2% of the GDP for the two territories, respectively. 12 Because of the availability of stone quarries and other sources of raw materials for building, combined with the significant Palestinian population growth, and augmented by construction of new Israeli settlements in the territories, the building industry continues to be more robust than other aspects of Palestine's industrial establishment. Additionally, a large proportion of Palestinians employed in Israel proper are engaged in the construction trades. Presently, Israeli policies considerably limit construction activities in the territories. Just getting the necessary permits is extremely expensive, both in time and money, and after all that, often fruitless in the end. Consequently, there is tremendous pent-up demand for new housing, infrastructure modernization and expansion, commercial facilities, etc. If an autonomous Palestine political entity emerges, a period of furious building is likely to ensue. Roads, water systems, sewers, communications links, businesses, government offices, power generating plants, ports of entry, and thousands of housing units will have to be constructed. One source estimates that in the first ten to fifteen years approximately 200,000 housing units will be required, the construction of which will employ initially 40,000 workers, and provide sustained work for an average of 25,000 a year over the extended period. Total development costs for infrastructure alone were estimated at over 13 billion 1990 dollars. Assuming a well-managed infusion of aid and capital, the construction industry alone could provide a vital boost to Palestine's economy for the foreseeable future. 13 AGRICULTURE For millennia, agriculture has been the primary industry in the Palestine region. It still ranks as the most important segment of the Palestinian economy, though total cultivated area has declined from 2,300 square kilometers prior to the 1967 war to 1,945 Square kilometers in 1989, and agriculture's share of local employment dropped from 43 percent (55,000 workers) in 1966 to 24 percent (40,000) in the mid-1980s. Relatively fertile land, generally available water supplies, and a warm climate promote a wide variety of agricultural products. Crops grown extensively include wheat, barley, olives, vegetables, grapes, and citrus fruits. Products from the livestock industry include meat from sheep, poultry, and cattle, as well as dairy products and eggs. 14 As one of Palestine's few significant natural resources, agricultural land is nevertheless poorly utilized. Water, of course, plays an important role. Though significant water resources exist compared to certain other areas in the region, supplies still have a finite limit. Disproportionate allocations to Israel have resulted in virtual stagnation in the expansion of irrigation for Palestinian agriculture. How important this is can be seen by the fact that in 1975, Gaza, with only one-tenth the cultivated land area of the West Bank, produced agricultural products valued at almost half that of the West Bank. Irrigation largely accounts for the difference--in the mid-1970s only four percent of the West Bank was irrigated, compared to about 45 percent of Gaza farmland. 15 By 1989, cultivated area in the territories had declined by almost 13 percent, while the proportional percentage of irrigated agricultural land has remained almost constant since the mid-70s. 16 Ironically, there is probably enough water available to increase dramatically the volume of irrigated land in the territories, and still supply domestic requirements. Inefficient water use and obsolete water management practices by the Palestinians contribute to the situation, but the most significant problem is the over-appropriation of water by Israel. By way of comparison, per capita consumption of water for Israel is between three and four hundred cubic meters, while it hovers at 100 cubic meters annually for Palestinians. Since 1967, Israel's water consumption rate has increased by 400-500 million cubic meters (mcm); that of the Palestinians by only 20 mcm. Even in Jordan per capita water consumption level is twice that of the territories. Israel has four times of irrigated land per capita than the territories; 95 percent of Israeli land available to irrigation is watered, compared to only 25 percent of what could be irrigated in the territories. 17 Water is not, however, the only obstacle to full use of Palestine's agricultural resources. While progress has been made over the years, many farmers still use archaic, traditional methods which waste much of the potential of that percentage of the land that is agriculturally developed. The improvements resulting from even the relatively limited agricultural education programs available and the efforts of a handful of Palestinian and Israeli extension service specialists show what could be accomplished with a fully supported effort. 18 One authoritative source lists five constraints on agricultural development:

Fortunately, few of these "constraints" are immutable. Most will prevail at the beginning of Palestine's transition from occupied territories to autonomous state, but will immediately begin to be alleviated as development programs are introduced. The very process of removing these constraints will actually infuse resources into not only the agrarian sector, but the Palestinian economy as a whole. Development plans are already being discussed; institutions and infrastructure can, and undoubtedly will be built; agricultural education and extension service programs can be introduced and expanded; land reform, capitalization, and commercial development can modernize the land-ownership system. The only constraint not directly remediable is the shortage of easily cultivated agricultural land. It is estimated that up to one third of the total area of Palestine, or--very roughly--2,000 square kilometers, falls into this category. Some of this land is on steep terrain, some is alkaline, some inaccessible, while much of it just receives too little rainfall and yet is not commercially accessible to irrigation projects. Improved technology, infusions of capital, further development of water projects, innovative cropping techniques, and introduction of new plant species will all contribute to the productive use of this land in the future. Of course, all these factors will also dramatically increase the productivity of the land that already is successfully farmed in the territories. Wider use of drip irrigation, shift in emphasis to crops with low water requirements, coastal aqua-culture, plastic greenhouses, and improvements in agricultural marketing are just a few of the suggestions proposed for improved agricultural production. 20 The goal of course, would be to approach self-sufficiency in food production for national consumption, balanced with creation of revenue through the agricultural export market. To get an idea of what domestic self-sufficiency entails, the Peoples Republic of China, which claims to be self-sufficient in food, cites the figure of .16 acre per person required to feed its population. The corresponding figure for the US is 1.6 acres per person, or ten times as much. Though American agriculture is among the most productive in the world, there is quite a divergence between the figures. The gap between the two statistics is explained by the fact that America's diet is high in meats and processed foods, which require more acreage to support. The rest of the world falls somewhere between the US and China. A reasonable figure for Palestine might be about .8 acres per person. For a population of 4 million, 3.2 million acres would be required, or approximately 1.28 million hectares, which is roughly 12,800 square kilometers. 21 Since with even the most efficient methods and best land reclamation programs Palestine could at the very most farm only 4,000 acres, the country will likely never be self-sufficient in food production. Yet Palestine can still meet many of its needs both domestically and for foreign exchange through its agricultural sector. The more that is produced at home, the less the country will have to depend on outside sources. FINANCIAL INFRASTRUCTURE Ironically, the financial structure of a country's economy is one sector that cannot be established or fixed just by "throwing money" at it. The mechanisms must be in place in order to effectively transfer, lend, deposit, monitor, manage, and disburse the funds that represent a state's life blood nationally and in international commerce. A nation-state with funds but without essential financial institutions, networks, and regulatory mechanisms is like a person with food but no digestive system. Unfortunately, that is precisely the situation in which Palestine--were it to emerge today--would find itself. Banking Banking services in the occupied territories are severely limited. Prior to the 1967 war, banking activity was conducted through 26 branches of eight Arab banks. Under the occupation, Israel eliminated these banks, allowing Israeli banks--with many restrictions--access to the territories. In 1981 the Bank of Palestine was allowed to open in Gaza, and branches of the Cairo/Amman bank have since reopened, subject to a variety of restrictions and regulations imposed by the military government. 22 To a significant degree, many of the Palestinians' banking needs are met by Palestinian money changers, who continue to serve such vital functions as currency exchange, money transfers into and out of the country and cashing bank drafts drawn from banks in Jordan and elsewhere. Nevertheless, the inadequate and patchwork variety of banking services continues to fall short of Palestinian needs, and could in no way adequately support the financial demands of progressive development, whether as part of a newly-autonomous Palestinian state, or even as a result of some hypothetical loosening of Israeli constraints on development in the territories. In order to meet those demands, a series of banks--privately organized but officially regulated--would need to be established. Entrepreneurial Palestinians with banking and financial expertise, once given the opportunity, are likely to jump at establishing new financial institutions. Fortunately, since such institutions require no intrinsic natural resources, nor in today's world are they particularly geographically dependent, they can be readily established given available money and places to use it. Extremely important, however, is the establishment of a well-regulated central national bank, essentially independent of political influence, act as a moderating influence on the banking industry and economy. Political meddling has historically contributed to high inflation and financial instability. Financial Reserves and Capitalization It is a foregone conclusion that Palestine will need major infusions of capital and aid from outside to bring it to a point where it can stand on its own--there just is not enough money available in the entire Palestinian community to approach the magnitude required to fund a reasonably expeditious development program. Nevertheless, Palestinians are not completely without resources. In the decades since banks were closed after the 1967 war, what investment occurred came from the resources of moneylenders and the savings of frugal Palestinians. 23 Economic repercussions from the intifada have drained these sources somewhat, but what remains will be available for use in a more benign development climate. A perhaps more important source is the PLO itself. The organization has assets that are variously estimated from $2 to $16 billion. It also has a well established fund-raising apparatus that--since the PLO's structure and resources will probably be largely assimilated into the government--would presumably be inherited by Palestine. As of this writing, of course, the PLO has fallen on hard times due largely to Arafat's incredibly bad decision to support Iraq during Desert Shield/Storm. Saudi Arabia and other Arab governments who had bankrolled the PLO for years seriously reconsidered their contributions and scaled them dramatically downward. This effect has been aggravated by a general drop in income for most of the region's economies due to lower oil prices and increased development costs. Not only are Arab governments less able to give, but many Palestinian expatriates were thrown out of work or continued on with reduced income, drastically reducing the remittances traditionally returned to families in the territories. 24 One final potential source within the Palestinian community for development funds and investment resources is more well-to-do Palestinians abroad in the diaspora. While large numbers of Palestinians live in poverty, there are still many who have prospered in enterprises and professions either in the Mid-East region or elsewhere in the West. Once a state is established and some stability achieved, these individuals may be willing to become financially involved in Palestinian development. In the end, none of these sources--even collectively--can satisfy Palestine's expected demand for development capital and investment. Ultimately, nations in the region and world--perhaps through the auspices of the United Nations--will have to contribute if Palestine is to get off the ground. Such assistance need not always be in the form of outright grants. Much, if not most, of the development will involve programs and projects that have potential for significant return on investment. Once a reasonably safe investment climate is established, there is real potential for entrepreneurs and venture capitalists to invest in the Palestinian economy. Development will not be cheap. One 1990 estimate concluded that social and physical infrastructure development alone would cost more than $13 billion, while developing the industrial, agricultural, commercial, and trade sectors would require another $10 billion, all over the course of ten years. 25 Another ten-year estimate proposed an ultimate cost in the neighborhood of between $30-$35 billion. 26 Nowhere near this entire sum will need to be directly injected into Palestine. Infusions of capital for major development programs will tend to "recycle" through the economy, fueling at smaller and smaller levels development in the service and commercial sectors as money passes through the hands, pockets, and bank accounts of Palestinian citizens. An ideal economy would function much like a terrarium, with resources cycling through various stages inside its hermetic container, requiring periodic input from outside to replace resources lost to entropy. Of course, no economy in the real world works perfectly this way--there are always leaks, and something must eventually be sent out to pay for what comes in. Many economies can't put out enough to balance what comes in, and must rely on assistance from better-off nations to balance their books. Some must come to rely heavily on export/import relationships. Palestine will probably turn out to be one of these, heavily dependent on its success in developing lucrative enterprises with products or services in demand in the international market place. Palestine's economic goal will be to make its requirements for outside assistance as small as possible, once its economy finally matures. Still, relatively huge sums will be required up front to get the nation's economy started. One must consider, though, that these investments would be made over several years and come from many different sources. And when one thinks by comparison of the amounts expended elsewhere in the world in support of other aid programs, the cold war, various arms races, and indeed, the on-going expense of the Palestinian problem if it is not resolved--the magnitude of the figures needed to develop Palestine seem less imposing. We might consider a jet engine as an analogy to what should happen with the Palestinian economy--one cannot just "turn on" a jet engine. Some sort of auxiliary power unit is needed to spin the turbine and compress the air and fuel to burn effectively. Once the engine is up and running, the auxiliary power unit is no longer needed. The engine now produces all the power it needs, and in fact can then be used to recharge the auxiliary unit. Currency Presently, the Jordanian dinar remains legal tender in the West Bank. Many financial transactions, however, must be conducted with Israeli currency. 27 Because of the habitual inflationary fluctuations of Israeli and Jordanian currency, it would be beneficial to divorce Palestine from the dinar and Israel's pound as soon as possible. Since having one's own money is a prominent symbol of national sovereignty, it is important that Palestine have a stable currency as soon as is practical once independence is achieved. However, rushing in too soon and ending up with unstable, inflation-ridden money would be detrimental. In event of a need for a currency transition period, it might be useful to temporarily adopt a relatively stable foreign currency, such as the US dollar, as backing. COMMUNICATIONS AND TRANSPORTATION INFRASTRUCTURE. Communications:

Transportation:

Building an airport is also fairly straightforward, but is further complicated by the need to obtain a large enough plot of ground, and to negotiate flight corridors and air space, particularly in light of the close proximity of various, not necessarily friendly, international borders. The above-mentioned proposal--to expand Qalandiyah airport--seems a marginal solution. Already crowded terrain in the West Bank would have further demands made on it, plus overflight of Israel would be unavoidable, and the proximity of Syrian, Lebanese, and Jordanian airspace complicates things. A more attractive solution might be the annexation or leasing of land from Egypt near the borders of the Gaza strip and construction of a full-service international airport there. This would offer several advantages. Even at only a modest leasing price, Egypt would gain a welcome source of badly needed income. No additional land area would be required from the already short supply in Palestine. Flight approaches could be made over the Mediterranean, vastly simplifying the overflight problem. And construction and operation of the airport would bring valuable employment opportunities to Gaza, where unemployment is highest. Direct, efficient road and rail access to the West Bank could link the airport with the largest part of Palestine, and Qalandiyah could remain as a regional-airport link to the primary international airport. Such a leasing arrangement is not without precedent. The Basel, Switzerland airport is located across an international border on leased property near Mulhouse, France. Also as mentioned above, Gaza has often been suggested as the site for a modern seaport. Construction of such a port is both technically and commercially feasible, and would give Palestine an essential outlet to the sea, removing it from dependence on the whims and fees of second-party nations for transshipment of goods and commodities. These proposals are, of course, absolutely dependent on a physical land-link between Gaza and the West Bank. Without it, Palestine would find survival almost impossible. Existence of this link hinges on whether or not Israel is amenable to granting the necessary right of way. The concept of such a corridor is also not without precedent. West Berlin survived for decades at the end of a two-hundred mile long corridor across hostile East Germany. It would be helpful if the link between the two parts of Palestine was less fragile than was the Berlin corridor, however. Today, it is feasible to provide such a corridor while creating minimal disruption for the Israelis. The corridor would require at a minimum a superhighway, freight and high-speed rail lines, and pipeline rights-of-way. To limit the impact on Israeli access between the coastal region and the Negev and limit points of friction or contention between the two countries, portions of the corridor could pass underground. In light of the recent opening of the "Chunnel" between Great Britain and the Continent, in the extremity it would even be technically feasible to put the whole corridor underground, though it would also be far more expensive. COMMERCE AND TRADE Exchange of goods and services provides the dynamic energy that fuels modern world and national economies. To ensure economic health and success, a state must have commodities, products, or services that others want to purchase. As discussed, the presence of these is a function of available raw materials, degree and efficiency of industrial development, availability of financial mechanisms, and transportation means to facilitate exchange of goods, commodities, and services. Though the potential for each of these elements exists, and is some cases is quite promising, all of them await significant development. Still, the present-day territories have at least a place from which to start. Farm products are the traditional foundation of Palestinian trade. Even after the occupation, the territories have regularly exported agricultural products to Jordan and, to a degree, to Israel as well. Recently, after a long battle with Israeli policies and bureaucrats, direct export of citrus crops to the European Common Market from Gaza has begun. 35 At present, except for human resources, there is little else of exportable value available in Palestine other than relatively low-revenue quarry products and potash, which would face stiff competition from Israel and other suppliers. As mentioned above, human resources have been an important Palestinian export in recent history, particularly laborers to Israel and workers to the oil fields and infrastructures of the Gulf states. The Gulf War and the intifada have both curbed the external market in Palestinian labor. Once a stable Palestinian state is established, however, expatriate Palestinians might again be favorably considered as employees in other Arab states. In Israel, the influx of former Soviet Jews may have an impact on the labor market, but there would likely be still some market for Palestinian laborers. This latter consideration presupposes some sort of open peace between Palestine and Israel. The shape of the final peace agreement negotiated between the two will be a major determining factor as to the character and degree of economic cooperation between Palestine and Israel. Greatest economic sense would be made by establishment of some sort of common-market-like arrangement among the immediate neighbors. It remains to be seen, however, if long-standing distrust and animosities can be set aside in favor of the best long-term interests of the region. For Palestine, however, success does not hinge on this. While an equitably managed Israeli-Palestinian-Jordanian common market could greatly speed Palestine's economic development (albeit at the cost of a certain amount of economic independence), with reliable air and sea access the new state would have less need to rely on either Israeli or Jordanian cooperation to succeed economically. With the new citrus fruit export arrangement, the territories already have a foothold in the door of Europe. It should be possible to expand this into a broad and healthy trade relationship. Important as it is, agriculture will be totally inadequate to provide the entire volume and value of foreign trade that will be required. Palestine is a prime candidate for the same sort of export-oriented, manufacturing-based economy as Japan, Taiwan, Singapore, Korea, or Hong Kong. High-tech and consumer goods, expanded textile manufacturing, durable goods--perhaps even to include heavy equipment and automobiles--are all plausible activities in which Palestine could profitably engage for trade in the world marketplace. Palestine could also assume at least part of the role formerly performed by Beirut of being the financial/banking capital of the eastern Mediterranean. Tourism, already an important industry for both Israel and the territories, would expand dramatically in the event a secure peace is established in the region. And as relations (hopefully) ease over the years following a successful peace agreement, Palestine could well become a major trade intermediary between the Arab world and the West, to include perhaps even Israel. WATER AND POWER DISTRIBUTION INFRASTRUCTURES Water Most of Palestine's water comes from wells throughout the West Bank and Gaza. Water supply and distribution is managed largely by local city and village councils, though there are a number of organizations such as the West Bank Water Department and the Ramallah and Bethlehem water authorities which exist to manage water use in specific areas. UNRWA supplies its refugee camps. Jerusalem's water is managed by the Israeli Jerusalem Municipality, and all water management is directly supervised and controlled by officials of the Israeli Water Department and "Mekorot," the Israeli Water Company. In the West Bank, 42 percent of domestic and industrial water is produced from municipal wells, 14 percent from private wells and springs, and the final 44 percent comes from Israeli-controlled sources. In rural areas of the West Bank, some 38 percent of the population has no access to water distribution systems, and Israeli-controlled sources provide 53 percent of the available water. Leakage and pump inefficiency lose from 30 to 50 percent of the total water supply. 36 Though the full dimensions of the water problem are discussed under Natural Resources, the implications of Palestine's present circumstances are that water distribution suffers from organizational and jurisdictional inefficiencies, Israeli exploitation, old or poorly maintained physical plants, and inadequate resources. It further sorely needs expansion to connect with a large portion of the population presently without service. Under current conditions, the Palestinian water system could not support rapid industrialization, nor expansion of intensive agricultural methods. Power Not even five percent of the electrical power used in the territories is generated by sources in Palestine. Two plants--one in East Jerusalem and one in Nablus, provide the greatest capacity, but their equipment is old and poorly maintained. The vast majority comes from the Israeli power grid. A number of rural communities have small generating facilities that provide part-time power. Altogether, 95 percent of urban dwellers have adequate access to electrical power, while only about 45 percent of rural areas have access to electricity. Industry consumes only 10 percent of the total available power. 37 Electric power and other sources of energy may prove the greatest immediate obstacle to development in event independence is achieved. Any peace agreement will have to specify a plan to gradually wean the West Bank and Gaza away from dependence on Israel. Alternative provisions for importing fuel for power generation will be necessary to lessen vulnerability to potential economic blackmail. The port in Gaza will play an important role here. An interim provision for temporary access to the Jordanian power grid could help partially alleviate the problem. Diversification of power sources would also help, and, fortunately, several ideas have surfaced. One suggestion is a Red Sea-Dead Sea canal. A waterway carved from the Gulf of Aqaba to the Dead Sea would take advantage of the 1200-foot differential between the two bodies of water. This would have the further advantage of providing interior access to sea water for desalination. The volume of water thus made available for hydroelectric generating potential would be limited by the evaporation rate of the Dead Sea, combined with the desalination capacity of any plants that might be constructed for that purpose. This concept is presently only notional, since cooperation between Jordan, Palestine, and Israel would be essential, and if that obstacle can be hurdled, the plan might still founder on technical, economic, or environmental grounds. Other options might be to pipe in natural gas from Egypt, to build an oil pipeline from Saudi Arabia or Iraq, and to construct a refinery in Palestine to process crude oil brought in by tanker or by pipeline. 38 Palestine's solar power potential is considerable, as well. While solar applications have grown markedly cheaper over the years, the technology still remains quite expensive for all but specialized projects. Imminent breakthroughs in alternative energy, however, promise to make such approaches cost-competitive in a decade or less. From the above discussion concerning aspects of the various infrastructures essential for a modern nation-state, it is apparent that Palestine will emerge with many immediate shortcomings. This, of course, will hamper development in the early stages. But from another perspective, having to "start from scratch" in building infrastructure may have significant benefits. One of these advantages is that properly planned and developed infrastructure will be new, state-of-the-art, and at the beginning of its life cycle. This fact can be very influential in facilitating growth and stimulating economic activity. Additionally, building infrastructure provides an extensive and fairly immediate pool of jobs at all levels of education and skill. Further, a major infrastructure development program provides a channel for pouring capital and external aid into the economy in a way that is less disruptive, provides for a reasonably natural economic growth in commercial and service industries, and avoids the "cloudburst" phenomena of large sums of money being "dumped" into an economy unable to assimilate it, like rainfall running off a parched field before it can soak in. Properly managed, infusions of capital and outside aid can build Palestine's roads, airfields, port, and communications networks while providing jobs, experience, and cash flow to jump-start the economy. ASSESSMENT Of all the factors of Palestinian viability, the economic is the most dependent on external input. As the above discussion has shown, outside capital is essential to accomplish anything substantial in building the State of Palestine. Because of that fact, this assessment alone will provide two figures for each of the subfactors except workforce (since that remains essentially the same regardless of capital infusion): one assuming capital and aid from outside the state, and the other assuming no capital input.

NOTES

United States: 254.5 million/6.366 million kmCIA, 123, 373. Lesch, note 70, p. 152. "Masterplanning," 73-74. Lesch, 106. "Masterplanning," 77-79. "Masterplanning," 79. "Masterplanning," 79-81, 173-174.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

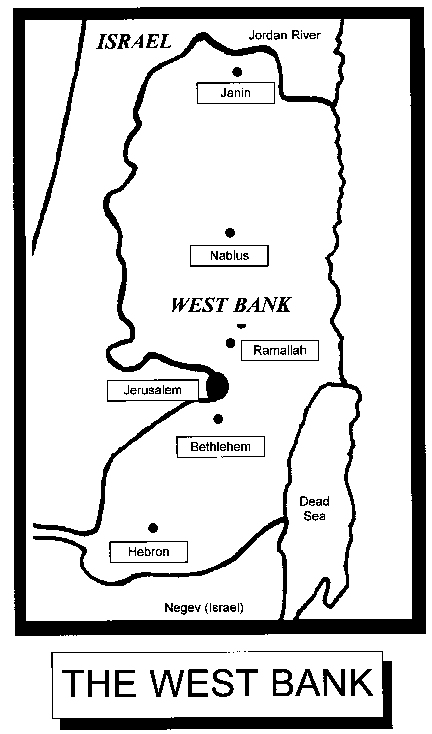

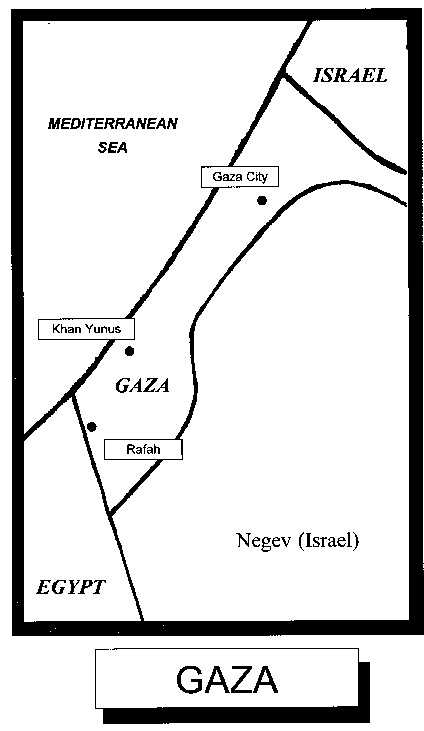

The first passes through the Jordan River valley, while the second forms an axis connecting Hebron, Bethlehem, Jerusalem, Ramallah, Nablus, and Jenin. The major north-south road for Gaza connects Khan Yunis with Gaza City, then continues out of the territory, passing through Israel to connect with the West Bank. Small portions of these main routes are four-lane divided highway, the remainder being two-way, two-lane macadam roads. The two primary highways in the West Bank are connected east and west to other areas of the territory through a network of smaller secondary, and small, poorly maintained local roads.

The first passes through the Jordan River valley, while the second forms an axis connecting Hebron, Bethlehem, Jerusalem, Ramallah, Nablus, and Jenin. The major north-south road for Gaza connects Khan Yunis with Gaza City, then continues out of the territory, passing through Israel to connect with the West Bank. Small portions of these main routes are four-lane divided highway, the remainder being two-way, two-lane macadam roads. The two primary highways in the West Bank are connected east and west to other areas of the territory through a network of smaller secondary, and small, poorly maintained local roads. It is obvious from the present condition of Palestine's infrastructure that it would be unable to support the emergence of a viable modern state. To fully evaluate economic viability requires a projection of what is practically feasible for Palestine to develop with regards to road, rail, air, and sea links. Improving the road and highway network, of course, is relatively easy to accomplish. Once needed funds are acquired, road expansion is a straightforward matter of planning, obtaining the necessary rights-of-way, and carrying out the plans.

It is obvious from the present condition of Palestine's infrastructure that it would be unable to support the emergence of a viable modern state. To fully evaluate economic viability requires a projection of what is practically feasible for Palestine to develop with regards to road, rail, air, and sea links. Improving the road and highway network, of course, is relatively easy to accomplish. Once needed funds are acquired, road expansion is a straightforward matter of planning, obtaining the necessary rights-of-way, and carrying out the plans.